Art, the art world and the world

, an artist and at-large editor for Red Wedge magazine, reviews a new book on art in an expanded version of an article written for the International Socialist Review.

ART IS in crisis.

First of all, contemporary art exists in a world of multiple crises--a world of rapid industrialization (resembling something from a Dickens novel) as well as a world of "post-industrial" ruins. It exists amidst racism, sexism, inequality and economic chaos.

Contemporary art is also riddled with its own contradictions--related to the "real world" problems above. What is the role of art when its audience is a small minority of the general population? What is the role of art produced by an individual--or a small group--when millions of images are now instantly available at the push of a button? What is art's answer to the growing consciousness of social class, inequality, crass commercialism, racism, sexism and so on? How do art's "spiritual" roles--for lack of a better term--relate to its social roles and its present economic location?

For generations, art's answer to technological innovation was to make itself a radical laboratory for signification--as expressed in the modernist succession of avant-garde movements.

"The Art World"

In that process, something called the "art world" was created--a phenomenon that is actually a peculiar industry--peculiar for industrial capitalism in that it is characterized by autonomous commodity (art) production geared toward a boutique market (the art gallery), and given validation by a specialized group of intellectuals (in art schools, journals and museums, etc.).

The appeal of art has been the autonomy of the artist. As Julian Stallabrass writes:

The freedom of art is more than an ideal. If, despite the small chance of success, the profession of artist is so popular, it is because it offers the prospect of a labor that is apparently free of narrow specialization, allowing the artist like heroes in the movies, to endow work and life with their own meanings.[1]

The middle-class structure of the art world and the moral imperatives associated with art are often torturous for artists from working-class, poor and even middle-class backgrounds. The "starving artist" cliché is not just a cliché, especially in the United States, with its barbaric lack of a welfare state and pervasive anti-intellectualism. Artists in the U.S. are treated and seen as largely expendable. Moreover, the largest and most important institutions of the art world do not necessarily expect to pay for the artwork exhibited and collected.

In his book 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, Ben Davis cites a 1973 letter from filmmaker Hollis Frampton to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), protesting that institution's assumption that he would exhibit his work unpaid. Frampton invoked the 1961 death of his friend Maya Deren in New York City. Maya Deren, one of the most important post-war experimental filmmakers in the United States, died of an aneurism caused by extreme malnutrition.

Artists have consistently been drawn to radical politics--both because of their tenuous positions in society and also because of the nature of art. Artists are, however, confronted by the fact--as Davis writes--that there is "no elegant fit between art and politics." What art does well is not necessarily what a genuine social movement needs at any given moment. As Davis writes of the Arab Spring:

As images of Tahrir Square filled the airwaves I found myself writing to artists in Egypt for an article about how they were responding to the uprising. An Egyptian painter wrote back, chiding me via email and questioning the terms of the inquiry. "It's not about artists now," she wrote. "It's about all Egyptians.[2]

In other words, the most important thing for artists to do was get their asses down to Tahrir Square like everyone else. The immediate needs of the revolution dwarfed artistic concerns.

Of course, many artists and academics won't like this answer. Those who produce and love art often give it phantasmagorical qualities--for good and bad reasons. To paraphrase Terry Eagleton, talking (or writing) about art is not unlike discussing sex. The tendency is either to exaggerate or minimize its importance.[3]

This is partly because art itself is one of the basic necessities of life. Just like sex, art can provoke "magical" responses in the human mind. Ernst Fischer argued this came from art's development in tandem with human evolution as the projection of human agency (through labor) over that which was not yet mastered.

There is, however, another reason for confusion surrounding the importance of contemporary art. In recent decades, the rise of post-modernism--a confused set of ideas that emphasized the fragmentation of ideology and narratives--appeared to have "freed" art. It became an art world conceit that art could be anything--any signifier, artifact, object or idea.

Meanwhile, the exponential growth of art theory and criticism gave more and more importance to the role of artists and intellectuals. Some argued that in the supposed absence of a revolutionary proletariat, intellectuals and artists were the center of a new critical and oppositional praxis.

In truth, of course, art can't be anything--there is an arduous process (related to the growth of theory) that determines what goes in (and doesn't go in) the magic white cube. Moreover, the audience for visual art remains a distinct minority.

In the 21st century, art seemed to become simultaneously heavy (in its supposed world-historical importance) and at the same time unbearably light (in its open-ended practice and relatively small audience).

Davis describes post-modernism, revising Frederic Jameson, as the "cultural ideology of neoliberalism."[4] Post-modernism's emphasis on fragmentation, hostility to "meta-narratives" (especially Marxism), decentralization and hyper-subjectivity, fit perfectly with the globalization of capital and its squeeze on the working-class.[5]

This insight--borrowed in part from David Harvey[6]--is related to Davis's attempt to relocate art in relationship to social class--the central thrust of 9.5 Theses on Art and Class. At the same time Davis does not stop there. He unpacks related questions dealing with artistic form, content, sexism, racism, inequality and conceptualism.

I can't, of course, review everything that Davis writes here, so I will try to profile and comment on some of the questions and points that he raises.

"Aesthetic Politics"

One of the byproducts of art's current crisis is the phenomenon known as "Aesthetic Politics"--a concept that supposedly rooted in Walter Benjamin's writings, but that has been articulated (in a far different manner) in journals such as October and by the French philosopher Jacques Ranciere.

Ben Davis summarizes Ranciere:

At some undefined point in the past, we overestimated art's political role as a "consciousness-raising" tool; but the fact that art could change the world was an illusion, a dogmatic theory that seemed credible only because of the existence of powerful "actual social movements" which presumably were responsible for the actual world changing. Then, in a weird pivot, Ranciere declares that the key is to acknowledge art's political role is not crucially defined by its relationship to "actual social movements" but instead we need to redefine politics itself in such as way that it completely sidesteps any non-artistic question at all; "an artistic intervention can be political by modifying the visible."

What Ranciere does for political art is what Jean Francois Lyotard[7] did for philosophy. Beginning with an exaggerated sense of the subjective--in art and politics for Ranciere, in politics for Lyotard--the subjective and objective are then completely blurred and their distinctions made meaningless. All this is philosophical cover for political retreat.

Davis makes this clear in discussing the work of the late Chris Marker--the avant-garde French filmmaker responsible for A Grin Without a Cat (1977) and La Jetee (1962). A Grin Without a Cat was a film essay that examined the failure of world revolution to materialize in the 1970s.

In 2004, Marker produced a new documentary, The Case of the Grinning Cat, "a film that charted the appearance of a particular piece of surreal street art--a grinning, yellow cat--against the background of the political turbulence of antifascists and student protests in Paris in the early 2000s."

Davis argues that the 2004 film shows Marker's retreat from the actuality of revolutionary action: "Both the 60s and '00s images are often blurred or obscured, in classic Marker fashion. But in the earlier ones, the blurring represents being engaged in the action; in the later, it seems to represent distraction, engaging with the protest as a passing spectacle."

As Davis argues, Marker's films--whatever his political state of mind--are absolutely brilliant works of art. "Aesthetic Politics," however, is essentially a theoretical adaptation of radical currents in art to neoliberalism and post-modernism--making a virtue of genuinely felt despairs, reproducing them and disguising them as political action.

Actual Bourgeois Decadence

Twentieth-century Stalinism--physically and spiritually trapped by a complete lack of dynamism--decried every innovative product of modern art as bourgeois and decadent.

This was aimed, in part, to conceal official Communism's cultural failures. If the Soviet Union was historically superior, why did abstract expressionism originate in the center of world capitalism--in a city built around Wall Street's den of thieves? Why did the greatest anti-capitalist artists of Europe flee to New York instead of Moscow during the Second World War?

To speak of decadence in art is not to mime the Stalinist idea of decadence--formal innovation, free expression, gay sex, drugs or martinis, for example. It is to speak of actual decadence.

In contemporary art, a good deal of this decadence can be linked to the Saatchi brothers--the advertising tycoons who famously helped Margaret Thatcher become prime minister of Britain with their "Labour Isn't Working" campaign in 1979.

The Saatchi brothers also insinuated themselves into the art market of the 1980s, helping promote art stars like the "Young British Artists"--in particular, Damien Hirst in the UK--and before that, neoexpressionists like Julian Schnabel in the U.S.

To be clear, not all artists represented and collected by Saatchi fall into the same category. Anselm Kiefer, despite his silly remarks about German Chancellor Angela Merkel and problematic philosophical worldview, is easily the best painter alive today. Critics and artists have sometimes been too hard on some of the 1980s "art stars"--like Julian Schnabel--once promoted by Saatchi. Even Damien Hirst--perhaps the worst of the bunch--began his career producing truly interesting artworks.

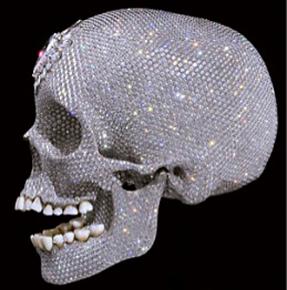

Hirst, however, long ago became emblematic of everything that is wrong with the art world. For example, Hirst's For the Love of God (2007) featured a platinum skull inlaid with 8,000 diamonds. It cost 14 million pounds to produce and sold for millions more.

Davis refers to Hirst and similar artists, quoting Joanna Drucker, as "complicit"--artists aiming to integrate themselves into the popular culture and its perceived titular decadence, rejecting the longstanding art world notion of independence (of some kind) from popular culture--an idea most fully articulated in the U.S. by the ex-Marxist art critic Clement Greenberg.

Hirst and other "complicit" artists have created mass events, crossover spectacles with the fashion industry, designed storefronts, handbags, consumer packaging, etc.--generally without any critique or "meaning" attached.

While these artists often look back to Andy Warhol, they lack the pathos and performance associated with Warhol's imperfect reproductions, tragedies, newspaper headlines, icons and celebrities. As Davis writes:

[A]rt's standoffish approach to popular culture is not merely a foolish set of ideas that can be waved aside. There has been, and remains, a quite real material basis for these ideas, a material basis that is threatened by mass culture, but that also continues to persist despite it. That explains art's enduringly lofty but also somewhat tortured and contradictory sense of itself.

Of course all art exists within a capitalist system, but the middle-class nature of art, petit-bourgeois structure and celebration of autonomy abhors the mass character of production tied to popular culture. This can be reactionary or elitist. It can also provide a space for a certain degree of intellectual and artistic freedom.

Rejecting the appalling products of complicit art, however, does not make one elitist, or mean that you are channeling the reactionary assumptions of Greenberg's formalism. Artists appalled by Hirst's For the Love of God can easily share their disgust with any workers that have encountered this prop for a latter-day Satyricon.[8]

More importantly, these decadent products of a soulless contemporary art are an affront to art itself--to the idea that art helps us complete ourselves in a way that nothing else can.

Art and Class

The starting point of most art criticism is the image or object. There is no problem with this per se. The problem comes when the work of art is left there, a free-floating sign separate from the rest of life. The subject of art becomes, too often, art itself rather than the "real world."

Davis also begins his book by discussing a work of art, but he brings it back into relationship with the rest of the world: Brooklyn artist William Powhida's How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality, an "Internet-age Daumier" drawing produced for the Brooklyn Rail. The drawing criticizes the New Museum's outsourcing of curatorial discretion to wealthy businessman Dakis Joannou and art world scourge Jeff Koons (who is only slightly less objectionable than Damien Hirst).

In 2010, at Davis's suggestion, Powida and artist Jennifer Dalton curated an exhibit in response to the New Museum. As Davis notes, class is often expressed in the art world as a reaction against the art market.

When the exhibit opened, Davis felt that the artists were struggling to find a language to discuss class beyond the art market. He wrote "9.5 Theses on Art and Class" and--channeling Martin Luther--taped them to the gallery door to provide a nuanced Marxist analysis of social class and contemporary art.[9]

There has been a great deal of confusion on this topic in "art circles," which tends to de-emphasize class and exaggerate individual subjective action. There has also been a tendency among artists to identify as working class for ideological reasons.

In fact, many artists are workers--but when they are working (as teachers, bartenders or gallery assistants), they generally aren't artists. Artists--inasmuch as they are artists--are middle class (in Marxist terms).

The entire structure of the art world is defined by its individualized relationship to commodity production. This is not a moral criticism of artists--who, as noted above, often face horrible material conditions. It is the best pivot point to understand art's relationship to the world, as Davis writes:

The middle class, by definition, is a middle term between labor and capital; if the reflexive need to elevate itself above "common" alienated work is one pole of its existence, a natural hostility to Big Capital is the other. (As a famous letter from King Leopold to Queen Victoria warns, rather amusingly: "The dealings with artists...require a great prudence; they are acquainted with all classes of society, and for that very reason dangerous.")

In a world as disenchanted as ours, desires to escape the routine humiliations of the economy are often channeled into the notion of becoming a visual artist. This investment can, in turn, imbue the profession with a genuinely radical character, making it a hospitable conductor for all kinds of alternative energies.

Indeed, beyond the bourgeois patron and the academic specialist, art audiences are drawn to art out of the need to escape the disenchantment of everyday life.

The art world, however, is unable to resolve its core contradictions. Ideas of craft, conceptualism, participation (the art world is still disproportionately white and male), radical gestures (street art, etc.) and collective action--all come crashing, again and again, into the realities of neoliberal capital and economic crisis. Only revolution will begin to resolve this.

The first step for artists in the here and now is to recognize that art is not just an intellectual game. Art must be more. Indeed, the language of contemporary art often fails to articulate the breadth of contemporary human experience and suffering. Art is "magic." But this magic only works in dialectical interplay with the narratives of actual life.[10] Separated from the real world, that magic becomes hollow and reified.

As Davis writes, "[A]rt is not a world unto itself. Art is part of the world. That fact has to be a fundamental starting point for everything."

Notes

1. Cited in Ben Davis, 9.5 Theses on Art and Class (Chicago: Haymarket, 2013). All quotes and references (without footnotes) to Davis are from 9.5 Theses. Stallabrass is a Marxist art critic known for his theoretical rigidity.

2. Ibid

3. Terry Eagleton, "The Death of Criticism," 2010 lecture at the University of California-Berkeley, available online at youtube.com/watch?v=QYHxGBH6o4M.

4. See Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991) as well as Ben Davis, "The Age of Semi-Post-Postmodernism," Artnet.com, 2010, available online at artnet.com/magazineus/reviews/davis/semi-post-postmodernism5-15-10.asp.

5. Neoliberalism is the name given to a certain set of economic policies characterized by classical monetary policies, "free trade," corporate globalization and policy shifts that prioritize capital over labor and finance over consumption. Neoliberalism became the dominant economic model in the 1980s displacing Keynesianism. Keynesianism was named after British economist John Maynard Keynes. It emphasized government spending and consumption as a means of staving off economic crises.

6. See David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991). Harvey argues that postmodernity is product of neoliberalism--in contrast to Frederic Jameson's argument that postmodernity the result of "late capitalism"--a somewhat confusing economic concept developed by the Belgian Marxist Ernst Mandel. Davis argues, however, that postmodernity is not a "natural" byproduct of neoliberalism but its ideology--implying a more conscious construction of postmodern ideas.

7. Lyotard was a Marxist and revolutionary who, in the wake of the defeats of the generation of 1968, became a leading post-modernist philosopher, particularly around questions of knowledge.

8. The Fellini film based on Petronius' novel Satyricon--the satire that skewered the decadence of Nero's Rome.

9. This story is recounted in Davis's 9.5 Theses. The original text can be found here.

10. Ben Davis does not necessarily share this position--it is based on the writing of Ernst Fischer, the Austrian Marxist literary and art critic, see Ernst Fischer, The Necessity of Art, (London and New York: Verso, 2010) (originally published in German in 1959).

This is an expanded version of a review that appeared in the International Socialist Review.