The politics of image and the image of struggle

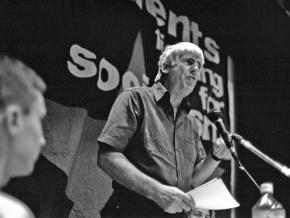

Paul Foot, who died in 2004, was a journalist, author and revolutionary socialist in the UK. As a member of the International Socialists and Socialist Workers Party, he is remembered as one of the finest writers and speakers for socialism in the postwar era. Earlier this year, the revolutionary socialism in the 21st century website republished the following interview with Foot conducted by James Bowen and Claire Donnelly for Impact, the University of Nottingham student newspaper, in 1996.

Foot was best known for his investigative journalism. Among the miscarriages of justice he uncovered was the Bridgewater Four, falsely convicted of murder in 1978, and the Birmingham Six, who were wrongly identified as responsible for an Irish Republican Army pub bombing campaign in 1974. His weekly columns in one of Britain’s major papers, the Daily Mirror, also brought attention to countless everyday cruelties inflicted on working class people by successive Tory — and Labour — governments. Foot always sought to reveal the irrational and iniquitous nature of capitalist society.

A tireless expounder of socialist ideas in books such as Why You Should Be a Socialist, Foot was also a captivating speaker. A fine example of his style can be heard in his discussion of the revolutionary poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The interview took place at the tail end of John Major’s Conservative Party government, a few months before New Labour’s landslide victory. It reflects Foot’s deep pessimism — borne out in reality — about the prospects for genuine change under Tony Blair’s leadership and more generally through parliamentary channels. One central focus is the revelations of the Scott Report into arms sales to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s by a UK company in defiance of a government ban that the Ministry of Defense itself had encouraged it to flout. This led to a political scandal and a public inquiry led by Lord Justice Scott, which issued its report in 1996.

One Foot in the Press

Paul Foot’s career as a journalist sees its 35th anniversary this year. Foot’s work in the media began in 1961 when he took up his first post as a reporter on the Glasgow Daily Record. A founder of Private Eye, he describes the satirical magazine as “free publishing of the most exhilarating kind.” His journalistic writings have been synonymous with his socialism. In 1963 he joined the International Socialists, forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party and joined the staff of Socialist Worker in 1968. Throughout the 1980s Paul wrote a regular page for the Daily Mirror, soliciting information from “people at the wrong end of society” and building up “an enormous and rich correspondence which tells the real story of what happened in the Thatcher years.” Paul continues to write for the Guardian and Socialist Worker, and contributes “Footnotes” to Private Eye. His literary criticisms include Shelley’s Revolutionary Year and the biography Red Shelley.

Foot on the Scott Report

YOU’VE WRITTEN a lot recently about the Scott report, and you seem to be saying that the most significant thing to come out of it is that it highlights the weakness of parliamentary democracy. You’ve also written about people’s loss of faith in the instruments of democracy, the civil service and so on. In the light of these concerns what are the implications of the report

I THINK the main thing about the 20th century, the main political point, is the increasing apparent impotence of parliamentary democracy. People fought for the vote. They argued that everyone had to have a vote, otherwise you couldn’t have a fair or legitimate government, and they won it. So people thought: you’ve elected the government and that’s it. My argument is that the country is run by a group of people who are there because of their economic interests. Those people are not there because they’ve been chosen by the electorate.

There’s a conflict all the time between the two, and one of the things that comes out very clearly in the Scott report is that it was the arms industry that shaped the decision-making process inside the government. Although it’s an elected government, the people who made the decisions about what arms should or should not go to Iraq, which is the question that was being addressed, were people who directly represented the arms companies. So you have a democratic government with a civil service, and people think the ministers and civil servants are making objective decisions on the basis of the general good. But in fact, the machinery of government in this case is almost entirely dominated by the arms industry. And this comes up all the time in Scott — the conflict was won by the people who have the economic power rather than the political power. Over and over again, the conflict is won in this way, and I think that’s really the history of the 20th century. The result of it is that people lose faith.

Here we are in Britain assuming, and I think rightly, that Labour is going to get into office with a huge majority. There was a time when a general feeling either for or against change would determine election results. This would follow a certain pattern across the world wherever you had democracies. That’s gone now. What you get now is people voting against the sitting government because the only thing they can do is vote against something, rather than for something. Because if you vote for something, nothing ever happens — unless you vote for the rich. And if you vote for the rich, the rich get what they want. If you vote for the dispossessed, for the poor and so on, you find that there’s no change. When there’s no change taking place people get disillusioned. Even in Spain, where you would have thought there’d be some continuity, the moderate socialist government has been thrown out [as a result of corruption scandals from 1993 to 1996]. That’s because people have lost their faith in the possibility that parliament can change things. This is why politics just degenerates into a sort of PR game — you know, Mandelson and Blair and all that rubbish. Can you smile more broadly? Can you make people believe that you can do things? It’s not a question of whether you can actually do anything, because no one believes it. So the question becomes whether your image is better. Politics just becomes a question of image and that’s what emerged very clearly out of Scott.

YOU’VE WRITTEN about the whitewashing of the real issues by many papers, including the Observer. What did you mean by that?

WELL, ONE problem with the report is that people didn’t have time to read it before they had to comment upon it, especially the Sunday papers. It came out on a Thursday night, and you had to get something in by Saturday. It was actually physically impossible for one person.

Another problem was that because people were dying for a couple of resignations from the government, for the government to be wounded in that way, and there weren’t any resignations. People reacted by saying the judge has sold out. Well, there’s no doubt he did let them off the hook to some extent, but the main point is that the report is an exposé of the system of modern government. The fact that Scott had cold feet about really going hard for these ministers so that they could be chucked out is of no significance compared to the general thrust of the report, which tells us how civil servants, ministers and arms dealers interact with each other in an entirely secretive form of government.

Foot on the Media

IF POLITICS is increasingly image-led, what role do you think the media play in it?

I THINK that the media plays a definite role. What you’ve got is a whole series of hierarchies which are controlled by wealthy people, not elected people. There are hierarchies in the fields of industry, finance, law and order, the police, army and media. They’re self-perpetuating and self-enriching. And their purpose is to do down the people who are actually producing the wealth. They’re all engaged in that — it’s a class operation.

Obviously, the media play a role because the media determine to some extent what we think. But I never go along with people who say that it is all the media’s fault, because the media just reflect the situation. They don’t actually change it. They keep it going, but they aren’t the only people responsible. If the rich are winning, then the media are extremely reactionary and right wing and hysterical. But if socialists start winning, the media change almost automatically. The front page of the Sun in the 1972 miners’ strike was an article by the general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers supporting the strike. In 1984, you would never have got a word in the Sun supporting the strike. The media aren’t constant. They change with the ebb and flow of what’s going on in a society generally.

Foot on Journalism

YOU ARE very critical of the way in which politicians and people working in the media use “jargon.” Your own writing tends to be very clear and accessible. Is that part of a conscious effort to avoid this perpetuation of hierarchies by the media?

IN GENERAL, the media are owned by big corporations, big monsters, who are as bad if not worse than any industrialist or banker. In fact many of them are industrialists or bankers. They perpetuate the status quo, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be a journalist who attacks the status quo. But you’ve got to work for people who are in favor of the system and so are suspicious of what you’re doing — much more so now than when I started off in this job.

People who want to be journalists but are against what’s going on can find it very difficult to get criticism of the way things are published. There is Nic [Cicutti] at The Independent, a financial journalist. He’s a member of the Socialist Workers Party, and that didn’t present a contradiction. Well, of course there is a contradiction, it’s difficult, but he was able to sustain the contradiction. It’s very difficult normally to be a journalist and to be a committed socialist. It’s very difficult to be anything and be a committed socialist.

The biggest decision I made in my life was to go and work on the Socialist Worker because that was a decision not to be a career journalist, not to try and become an executive. I’d just won an award here at Private Eye, and I established a new attitude toward investigative journalism, which was highly respected. Socialist Worker approached me and said, “Come on, work for us. We’ll halve your salary, and you can work on this paper that nobody reads, no one will ever hear you again.” It was completely irresistible. I’ve had a column in the Socialist Worker for 30 years now.

One of the problems for socialists is that they feel that it’s necessary to speak in a sort of jargon. I’m constantly criticizing my socialist colleagues for that. It’s not just writing, it’s also speaking. They slide into a sort of toneless noise which doesn’t bear any relation to the words which they’re actually saying. The words that they speak or write are often the wrong words because they’re simply repeating things by rote.

I suppose it must be a gift to have the ability to write clearly. It just seems to me to be quite natural, but I know a lot of people find it difficult. I wish it was a gift that more socialists had, because writing and speaking clearly is necessary in order to try and grapple with what your audience is actually thinking. I’m always trying to understand what are people thinking, what is going through their brains, and address that, rather than just hector and shout at people. That never actually sways anyone at all. If anything it puts them off.

I went to speak in an official lecture on the Scott report. It was at the Institute of Criminology, and it was absolutely packed. There were a couple of contributions there from members of the Socialist Workers Party, and even as they were speaking, you started to hear people laughing or tittering with embarrassment. Instead of actually addressing people’s state of mind, carrying them forward to a socialist perspective, they were just speaking to them from above. And that amuses and annoys people.

I thought that being a journalist would be more exciting than anything else, and I was completely right about that. You’re constantly engaged and the material you’re dealing with changes week by week. There’s a contradiction inherent in working as a journalist because you find try and find things out, scoops and all that. That’s good, because instead of just being told by the news editor what to do next, you can say, I’ll do this, and they hesitate because they think this might be something that will win the regional press award. You need to play on that contradiction.

Foot on Communication

IN THE introduction to your book Words Are Weapons [a collection of Foot’s journalism], you mentioned [SWP founder] Tony Cliff. In my opinion, he speaks to people in the way you’re suggesting we should aspire to. You end up asking yourself, “Why didn’t I see it like that?”

I AGREE. I’ve met an awful lot of famous people in my field, but this chap Cliff, who no one’s ever heard of, is streets ahead of anyone else. His gift is the ability to say things which make you think. When I first went off to be a journalist in Glasgow and met Cliff and heard what he was saying, it lifted a veil about the nature of the society we live in. That veil has never come down again. I often speak alongside him at rallies, and every time I do, I always think, I am really just gilding the lily here. I’m just painting a rhetorical picture on the argument we’re making, whereas he always comes directly to it.

That’s a completely different perspective from the bourgeois notion of oratory as something florid or showy. It’s like the famous argument between Edward Burke and Tom Paine. Paine comes along with direct, clear language for the people, and he says that Burke pities the plumage and forgets the dying bird. I think that exactly sums up this bourgeois Oxford Union notion that you should speak with grandiloquence and rhetoric.

HOW DOES the way you use humor relate to this idea of plain speaking? Do you consciously use humor as a way of reaching an audience?

I LIKE laughing at things myself, and I very much like hearing people laugh. My instinct has always to see the absurd side of things. Capitalism is a ridiculous form of society, as well as being monstrous. All the stuff that comes out of the Scott report is so funny apart from anything else.

If you think about it, when you’re speaking in public, the only way that you can get people to respond is by getting them to laugh. If it’s just a relationship where one person is active and everyone else is passively listening, the minute you get a laugh, then the whole relationship changes. People can be quite sour and sullen, not willing to respond. In the good days, in the 1970s, people would be laughing all the way through the speech. That would affect me, and lots of the things I said then were entirely spontaneous. The audience inspires you in the same way as you try to inspire them. I often look at people’s faces when I’m speaking, and I always wonder, are they thinking about the football match? Because I probably would be. If people feel they’re going to get a laugh, they’ll come to the meeting when they wouldn’t have otherwise.

I think that these things are terribly important. Actually, I’m a bit reluctant sometimes to raise them. People say that just because you can [use humor], you’re snobbish about it, and you’re a bit contemptuous of the comrades, which I’m not at all. I do think we’re inclined to be very undisciplined with ourselves about style and the way we do things like speaking. I went to a meeting in Liverpool, and I was amazed that about seven or eight comrades spoke after me, and no one else spoke at all.

Foot on Education

WHAT IS your view of the British education system?

I THINK an education system in a class society reflects the needs of that society. In a way, in Nottingham, you’ve got it clearer than anywhere else. You’ve got the two universities there, which perhaps more than in any other city in the country are entirely dominated by business interests, utterly and completely. They’ve gone out of their way to make new chairs.

For example, there’s a man called [Eric] Caines there. I think he’s at the University [of Nottingham]. He’s been given a chair in Health Service Management. He’s absolutely and utterly ideological on the question [of privatization of the National Health Sercie]. He’s a total and complete Thatcherite. And for him to be given a chair is clearly an example of latent political prejudice. What they teach under that chair, I dread to think.

Caines is a civil servant — you can look him up. He’s not a man who’s remotely interested in teaching people — that’s not been his career at all. If you look back at the various attempts to squeeze the National Health Service and batter it into submission, he will have been absolutely central to it from the start to finish. The whole business of the directorships of health care, the whole way in which health care has become a subject for education, is all to do with this general attack. Health Service Management — that will just be a privatization of the NHS jamboree. All the time, education is being colored by the political priorities of the ruling class.

My education started when I left university. I never learned anything in formal education. I did law at university, which was a complete and utter waste of time. I just did it because all my family had been lawyers. I was only halfway through when I thought, this is absolute rubbish, and I wanted to be a journalist, but I didn’t have the guts to change. I should have read politics or philosophy or something like that. I didn’t learn anything until I became a journalist.

WHAT ARE your thoughts on education funding?

I THINK there’s this idea that we can survive without having to provide the money for people’s education. We’ll cut the public provision and increase the private provision. They want to increase what individuals have to pay and go back to the days where families would put themselves in hock for the rest of their lives in order to send their children to university. They love the idea that you mortgage your life to a house, and then your house to your children’s education, and you haven’t got anything left over after that.

Foot on the Labour Party

I DON’T think anything will improve very much under Labour unless there is a movement from below. Everything depends on whether there are substantial numbers of people who are prepared to withhold their labor or activate themselves and demonstrate. Otherwise, events just proceed along the normal reactionary path, whatever government is in office. But when people have got rid of [John Major’s] government, they’ll expect things to get easier, and when it doesn’t, there is a chance there’ll be unrest.

The unexpectedness of changes is one of the things that keeps you going. Things are constantly changing — that’s the dynamic of a class society. One side is bullying, and the other side is receiving the bullying. It only has a vague connection with the government.