Revolutionary changemakers

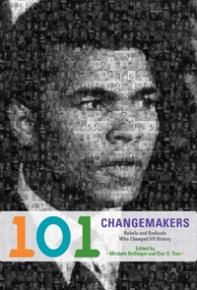

A new book written for middle-school students--101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History, edited by and --offers a "peoples' history" of some of the individuals who shaped this country. In the place of founding fathers, presidents and titans of industry, 101 Changemakers includes profiles of people who fought courageously for social justice. Every "changemaker" is remembered with a short biography and timeline of their life, plus suggestions for more to do and questions to consider.

SocialistWorker.org is publishing excerpts from 101 Changemakers all week. Today's focus is revolutionary voices in the struggles of the U.S.

Tom Paine

(1737-1809)

In January 1775, Tom Paine was just another poor Englishman sailing to the North American colonies in hopes of a better future.

One year later this English nobody became a hero by writing Common Sense, a short book that helped start a war for independence against the country he had just left.

Most famous writers in those days came from rich families, but Tom had to leave school at age thirteen to get a job. For twenty years he worked in England as a dressmaker and a tax collector, sometimes facing real poverty.

When Tom arrived in Philadelphia, colonists were angry about English taxes but still loyal to King George III. In Common Sense, Tom wrote that the problem was not the laws of the English king but that England had a king at all: "For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other."

Common Sense urged colonial settlers to create a republic, a government based on elected representatives of the people: "The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth." Written in a plain style for workers and farmers, Common Sense sold one hundred fifty thousand copies. Few other books have ever been bought by such a big portion of the American people. On July 4, 1776--six months after Tom wrote Common Sense--the colonists declared independence from England. Of course, England did not agree. The War for Independence lasted seven years and at first the small and poor Continental Army was in deep trouble.

Tom wrote a series of articles called "The American Crisis" to keep Americans from giving up by reminding them what they were fighting for. "Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered," he wrote, "yet the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. . . . Heaven knows how to set a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange . . . if freedom should not be highly rated." General George Washington found these words so inspiring he had them read to his soldiers the night before the important battle of Trenton.

After the war ended, many of the new nation's leaders were slave owners like Washington and wealthy lawyers like John Adams who did not want to see any more radical changes.

Tom was different. He saw the American Revolution as part of a worldwide movement for fairness. He wrote against slavery and poverty. When France revolted against its king, Tom moved to France and was elected to the new government even though he only spoke English. Later, when his allies lost power, he was thrown in jail and almost executed.

SocialistWorker.org is running excerpts from 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. HistoryFrom 101 Changemakers

In 1791 Tom wrote The Rights of Man to support the French Revolution. Two years later he wrote The Age of Reason to argue that society should be based on science rather than religion. Like Common Sense, these books were widely read by working people in France, England, and the United States.

These books, however, also made Tom many enemies who thought his ideas were dangerous to governments and religions. When he died in 1809 outside New York City, few people came to the funeral of one of the great leaders of the American Revolution.

-- Danny Katch

Timeline:

1737: Born in Thetford, England

1775: Arrives in Philadelphia

1776: Writes Common Sense, which helps convince American colonists to fight for independence from Great Britain

1776-83: Writes "The American Crisis" articles to inspire American troops during the Revolutionary War

1791-92: Writes The Rights of Man in support of the French Revolution

1792: Moves to France and is elected to the revolutionary National Convention

1793: Arrested and jailed when his allies in the French Revolution are thrown out of power, and is angry that President Washington doesn't do more to win his freedom

1793-94: Writes The Age of Reason in support of science and reason over organized religion

1794: Released from prison

1802: Returns to United States

1809: Dies in New Rochelle, New York

Helen Keller

(1880-1968)

Helen Keller is famous for her work as a disability rights activist. She wasn't born disabled, but became deaf and blind after she got very sick as a toddler.

Fortunately for Helen, her parents consulted many doctors and teachers, and she eventually learned to communicate. But she didn't do it alone. She might not have done it at all if she hadn't met Anne Sullivan. Helen's parents hired Anne as her teacher. Anne eventually broke through Helen's shell by spelling words with her finger on Helen's hand. One famous moment occurred when she made the connection between the letters (w-a-t-e-r) Anne was signing on her hands and the water falling on her other hand. Helen began to learn words and sentences. Then she began to communicate by signing the manual alphabet.

Helen attended Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She was becoming well known, meeting people like Mark Twain. She became the first deaf and blind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree.

As a disability rights activist, Helen was invited to speak across the United States and all over the world. But Helen's views were not limited to rights for those living with disabilities. She lived in a time of war and change, and she supported the labor movement and became a socialist.

Not everyone approved of this, however. For example, the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle disagreed with Helen's political opinions. He quickly reminded his readers that Helen was disabled. In his view, her politics were mistakes that "spring out of the manifest limitations of her development."

In her essay "How I Became a Socialist," Helen wrote: "Now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error. I must have shrunk in intelligence during the years since I met him...Oh, ridiculous Brooklyn Eagle! Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent."

Helen supported women's right to vote and opposed World War I. She supported Eugene Debs, who was imprisoned for his opposition to the war. In a letter to Debs in 1919, Helen said, "I write because I want you to know that I should be proud if the Supreme Court convicted me of abhorring war, and doing all in my power to oppose it. When I think of the millions who have suffered in all the wicked wars of the past, I am shaken with the anguish of a great impatience. I want to fling myself against all brute powers that destroy life and break the spirit of man."

Helen spoke out for social justice. She joined the Industrial Workers of the World and helped found the ACLU. Her legacy as a disability rights activist continues, but her life as a radical is an important part of her story that should not be forgotten.

-- Jessie Muldoon

Timeline:

1880: Born in Tuscumbia, Alabama on June 27

1887: Anne Sullivan becomes Helen's teacher

1903: Publishes her autobiography The Story of My Life

1904: Graduates from Radcliffe College, becoming the first deaf and blind person to earn a college diploma

1912: Publishes "How I Became a Socialist"

1916-18: Is an active writer for the Industrial Workers of the World

1919: Writes letter defending Eugene Debs and opposing his imprisonment

1920: Helps to found the American Civil Liberties Union

1936: Anne Sullivan dies

1961: Suffers a number of strokes

1964: Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Lyndon B. Johnson

1968: Dies in Connecticut