Anti-racist changemakers

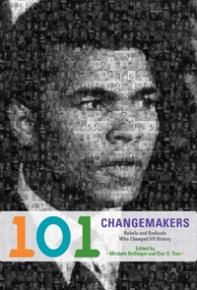

A new book written for middle-school students--101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. History, edited by and --offers a "peoples' history" of some of the individuals who shaped this country. In the place of founding fathers, presidents and titans of industry, 101 Changemakers includes profiles of people who fought courageously for social justice. Every "changemaker" is remembered with a short biography and timeline of their life, plus suggestions for more to do and questions to consider.

SocialistWorker.org is publishing excerpts from 101 Changemakers all week. Today's focus is revolutionary voices in the struggles of the U.S.

Nathaniel "Nat" Turner

(1800-1831)

Few enslaved leaders have become as legendary as Nat Turner. In 1831, Nat led an armed slave revolt in the small farm community of Southampton, Virginia.

"Turner's Rebellion" shocked the young American nation and warned of the coming civil war.

As was the custom at his birth in 1800, Nat was given the same last name as his "owner," Benjamin Turner. Nat's father escaped from slavery when Nat was just a boy. Nat's mother and grandmother raised him. His paternal grandmother's people were the Coromantee of Ghana. They were known as a defiant people who resisted enslavement. Nat lived up to this reputation.

Young Nat learned to read and write from the Turners. This was unusual for many enslaved people at the time. He used his education and deep religious beliefs to develop himself as a leader. He spent much of his time preaching to other enslaved people, who nicknamed him "the Prophet."

In the 1820s, Nat started hearing voices and seeing visions of black and white angels clashing in the sky. He believed God was sending him messages to "slay [his] enemies with their own weapons." After seeing a solar eclipse, Nat thought the time had come to rise up against the injustice of slavery. On August 21, 1831, he and several trusted fellow enslaved Africans began the deadly rebellion. They traveled from house to house, killing slave owners and their families with knives and axes. Freeing enslaved people they met, Nat and his band seized weapons, horses, and money. Nat led more than seventy rebels in this "explosion [of] black rage."

The rebels focused their rage on slave-owning households. They spared one home where a poor white family lived, and the home of Nat's childhood friend. White authorities wasted no time in responding. Militias were assembled and quickly surrounded Nat and the rebels. Within two days, several battles weakened and finally defeated the rebellion. However, it took twice as many white soldiers to defeat the small but defiant group of black rebels. Many rebels were captured and executed.

Nat himself escaped capture for two months. He hid in a small hole that he dug in a field. On October 30, a dog discovered his hiding spot and Nat was caught. He was quickly tried, convicted, and sentenced to death by hanging. The state of Virginia executed as many as fifty-one enslaved people for the rebellion, even though many were not involved.

The rebellion terrified white slaveowners in Virginia and beyond. Most thought that those they enslaved were less than human and were happy to be slaves. White people were shocked at how quickly the rebellion spread. After the uprising, harsh slave laws were enacted from Southampton County to Georgia, the Carolinas, and Alabama. After Nat's execution, the white population of Southampton went on a rampage. Mob violence killed close to two hundred black people in Virginia and North Carolina.

SocialistWorker.org is running excerpts from 101 Changemakers: Rebels and Radicals Who Changed U.S. HistoryFrom 101 Changemakers

Nat and the rebellion he led inspired those opposed to slavery. Long after the end of slavery, black leaders took inspiration from the strength and bravery Nat and his fellow rebels showed. Despite its bloody and failed ending, people would never forget Turner's Rebellion.

-- Zach Zill

Timeline:

1800: Born in Southampton County, Virginia, on October 8

1802-10: Father escapes from slavery

1821: Runs away but returns to the Turner farm after hearing a voice, marries enslaved girl Cherry

1822: Sold to Thomas Moore, who drives him hard as a field hand

1825: Begins conducting his own praise meetings

1827: Ministers to and baptizes a white man

1830: Moves to the home of Joseph Travis, husband to Thomas Moore's widow

1831: August 21, begins rebellion with other enslaved Africans after seeing solar eclipse; August 22, the group turns toward the county seat, Jerusalem, is confronted by militia, and scatters; August 23, several rebels are captured; the remainder meet in a fight with state and federal troops in which three die; October 30, discovered and captured; November 5, tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in Southampton County; November 11, executed

1832 Virginia, Alabama, and other Southern states enact laws forbidding the education of enslaved people

Claudette Colvin

(1939-)

Claudette Colvin grew up outside Montgomery, Alabama, with her great-aunt Mary Ann, great-uncle Q. P., and sister Delphine. The family moved there when Claudette was eight.

Claudette attended Booker T. Washington High School, where she first became an activist against racism. Her first campaign was around Jeremiah Reeves, a fellow student sentenced to death by an all-white jury for an alleged attack on a white woman. Claudette and other students rallied, wrote letters, and collected money on his behalf. Although Reeves claimed he was forced to confess to the crime, he was executed.

On March 2, 1955, fifteen-year-old Claudette refused to give up her seat on the bus for a white woman--nine months before Rosa Parks's similar action sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. Claudette remembers: "My head was just too full of black history...the oppression that we went through. It felt like Sojourner Truth was on one side pushing me down, and Harriet Tubman was on the other side of me pushing me down. I couldn't get up." She was dragged off the bus by two cops, arrested, and charged with violating segregation law, disturbing the peace, and assaulting the officers.

Important civil rights activists came to Claudette's aid. They included Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; Jo Ann Robinson, a leader in the local Women's Political Council; E. D. Nixon, a leader in the NAACP; and Rosa Parks. Fred Gray, Claudette's lawyer, hoped to use the case to end segregation on the buses. But Claudette was found guilty on all three charges. Later, through an appeal, all charges were dropped except the assault charge. She was put on probation under the custody of her parents.

Support for Claudette's case soon decreased. To some she seemed too "rebellious." Movement leaders stepped back from Claudette as well, seeing her youth as a barrier to winning changes on the buses. Claudette also became pregnant that year. At that time, people thought it was very shocking for an unmarried teenager to have a baby. Some in the movement thought that Claudette's pregnancy would make them look bad. She felt further shunned by her community.

In December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on the bus to a white person. This time, a boycott of the buses in Montgomery was organized through mass weekly meetings. Claudette had moved to Birmingham after learning she was pregnant, but returned to Montgomery to help organize the boycott.

In May 1956, Fred Gray filed a lawsuit, Bowder v. Gayle, against the state of Alabama, challenging segregation on buses based on the Brown v. Board of Education ruling against segregation in public schools. Gray called on Claudette and four other black women to be plaintiffs in the case. Their strong testimonies and the ongoing boycott pushed the Alabama court to find segregation on the Montgomery buses unconstitutional. Though Claudette is not well known, her courageous stance was one necessary spark of this victorious movement.

-- Akunna Eneh

Timeline:

1939: Born Claudette Austin in Birmingham, Alabama

1947: Moves to Montgomery with great-aunt, great-uncle, and sister

1952: Sister Delphine dies of polio

1952: Begins high school at Booker T. Washington High

1954: Brown vs. Board of Education outlaws racial segregation in public schools

1955: March, refuses to give up her seat to a white woman on the bus, is arrested and charged with violating segregation law, disturbing the peace, and assaulting an officer; later found guilty on all three charges; May, two charges are dropped at her hearing; she is placed under probation; December, Rosa Parks arrested after refusing to move for a white person on the bus; Montgomery bus boycott begins

1956: June, court rules segregation on buses in Montgomery is unconstitutional; December, federal marshals impose Bowder v. Gayle ruling in Montgomery, forcing integration of the buses, and the boycott ends