Reconstruction after the war

tells the story of the aftermath of the Civil War and the brief attempt to "reconstruct" the U.S. South on the basis of democracy and political equality for the freed Black slaves, in the final installment of an SW series on slavery and the Civil War.

THE FORMAL emancipation of African American slaves and the victory of the Union Army in the Civil War constituted a significant but incomplete advance for the U.S. working class.

As the historian Eric Foner wrote, African Americans carried out of slavery "a conception of themselves as a 'Working Class of People' who had been unjustly deprived of the fruits of their labor." With the abolition of slavery--the largest expropriation of private property in history to that point and for many years after--the potential was created, for the first time in U.S. history, for a mass interracial working class movement.

At the same time, the leading role of Northern industrialists in bringing about the end of slavery represented a bourgeois revolution seeking to unshackle the productive forces of U.S. capitalism and expand its reach, both domestically and internationally.

Karl Marx, a passionate opponent of slavery and supporter of the North during the Civil War, had foreseen this as the likely and necessary outcome of the Civil War. After learning of Abraham Lincoln's reelection as president in 1864, Marx penned a congratulatory letter to Lincoln in the name of the newly formed International Workingmen's Association--which came to be known as the First International:

While the workingmen, the true political power of the North, allowed slavery to defile their own republic, while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master, they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor, or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation; but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.

The workingmen of Europe feel sure that, as the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American anti-slavery war will do for the working classes.

Or as Marx put it in a letter to his collaborator Frederick Engels, "After the Civil War phase, the United States are really only now entering the revolutionary phase, and the European wiseacres, who believe in the omnipotence of [President Andrew Johnson], will soon be disillusioned."

The period that followed, known today as Reconstruction, was the battleground in that struggle.

One hundred and fifty years ago, the institution of slavery was finally destroyed with the end of the Civil War. Socialist Worker writers tell the story.

Slavery and the Civil War

Slavery and the roots of racism

The resistance to history’s enormous crime

The road to the Civil War

To save the Union or to free the slaves?

The Civil War becomes a revolutionary war

Reconstruction after the war

Reconstruction was the name for the U.S. federal government program that was ostensibly to rebuild the South after the end of slavery, transition slaves to freedmen and reverse historic discrimination against African Americans.

In practice, Reconstruction resulted in a series of radical reforms that workers fought for and used to advance control of their lives and the labor process further than at any point in U.S. history. Yet for the reasons discussed below, Reconstruction was ultimately a failed revolution.

FOR NEWLY freed Black workers in the South, class consciousness and a desire for self-determination came swift. Told by his white planter boss, "You lazy n*****, I am losing a whole day's labor for you," a freedman replied, "Massa, how many day's labor have I lost by you?"

Under the protection of Reconstruction programs--and, critically, federal troops dispatched and stationed across the conquered states of the defeated Confederacy--Blacks acquired land for themselves; negotiated new tenancy contracts, and raised money to purchase land, build schoolhouses and hire teachers. By 1870, African Americans had spent more than $1 million on education. The newly formed Freedmen's Bureau, meanwhile, issued more than 21 million rations to the hungry and unemployed, three-quarters to African Americans and one-quarter to whites.

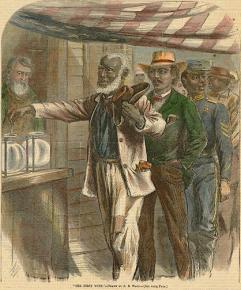

The Radical Reconstruction wing of the Republican Party, led by men like Thaddeus Stevens, fought for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which outlawed any attempt to withhold citizenship, equal protection under the law and voting rights based on race or other factors. For the first time in U.S. history, Blacks voted in massive numbers, with turnout approaching 90 percent in many elections. Black candidates were elected to local, state and federal office, including two U.S. senators from Mississippi.

At the same time, a northern and predominately white labor movement, agitated by increased wartime production, took forward steps.

The first national organization of trade unions was formed one year after the end of the Civil War. The inaugural session of the new National Labor Union took place in August 1866 in Baltimore. It placed the fight for an eight-hour workday--launched during the war--at the center of labor's demands and insisted that Black workers be included in the new Union.

These simultaneous developments were described hopefully by Marx in Capital Volume 1, published in 1867, the second year of Reconstruction:

In the United States of America, any sort of independent labor movement was paralyzed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the republic. Labor with a white skin cannot emancipate itself where labor with a black skin is branded. But out of the death of slavery, a new and vigorous life sprang.

Yet the challenges to this "new and vigorous life" were many. First, as Eric Foner noted, the Southern planter ruling class "had no intention of presiding over its own dissolution." It supported Northern investment in the South only insofar as it was able to keep control over the Black labor force.

Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Abraham Lincoln as president after Lincoln was assassinated within days of the official end of the Civil War, had been named the Republican Party's vice presidential candidate to try to win pro-slavery votes in the North and Border States during the 1864 election. Johnson was a racist reactionary and opposed to the so-called "Radical Republicans," as the wing of the party led by Stevens and others was known. Johnson vetoed civil rights legislation passed by the Radical Republicans--his aim was to help preserve the land and economic rights of the Southern gentry.

Southern Democrats, meanwhile, attempted with some success to split the Radical Republican coalition by separating African Americans and native whites from political leaders--known as "carpetbaggers"--who were associated with the federal government's occupation of the South. Beyond this, however, the planter class attempted to split Blacks and poor whites by promoting outright white supremacism and ideas about the racial inferiority of Blacks.

THE CONFLICT between workers' desire for enhanced freedoms and capital control produced what W.E.B. Du Bois called, in his masterpiece Black Reconstruction in America, a "counter-revolution of property."

Du Bois argued that both the Civil War and Radical Reconstruction reflected the pressures of Black and white workers' resistance to slavery and oligarchy as systems of labor exploitation. Both Black slaves and poor white farmers, Du Bois pointed out, had fled the plantations during the war. Some 200,000 African Americans also fought in the Union Army, helping to turn the tide against the Confederacy.

"Abolition democracy" was Du Bois's name for the interlude of Reconstruction. It produced what he called a temporary "dictatorship of labor" in the South, imposed by the Reconstruction government.

Du Bois then showed how capitalist imperatives destroyed this period of radical reform. Postwar Northern industry found itself, Du Bois wrote, with "a vast organization for production, new supplies of raw material, a growing transportation system on land and water, and a new technical knowledge of processes." The potential for profits overrode any provisional ruling class commitments to social, racial or economic equality. As Du Bois put it:

Far from turning toward any conception of dictatorship of the proletariat, of surrendering power either into the hands of labor or of the trustees of labor, the new plan was to concentrate into a trusteeship of capital a new and far-reaching power which would dominate the government of the United States.

The end of Reconstruction came in 1877, when Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South in exchange for the Democrats' support for their candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, in the contested presidential election of 1876. Du Bois' analysis of the end of Reconstruction was acute:

The bargain of 1876 was essentially an understanding by which the federal government ceased to sustain the right to vote of half of the laboring population of the South, and left capital as represented by the old planter class, the new Northern capitalist, and the capitalist that began to rise out of the poor whites, with a control of labor greater than in any modern industrial state in in civilized lands...

The new dictatorship became a manipulation of the white labor vote, which followed the lines of similar control in the North, while it proceeded to deprive the Black voter by violence and force of any vote at all. The rivalry of these two classes of labor and their competition neutralized the labor vote in the South...And the United States...took its place to reinforce the capitalistic dictatorship...which became the most powerful in the world, and which backed the new industrial imperialism and degraded colored labor the world over.

Du Bois' rendering of Reconstruction was revolutionary and of lasting importance in helping socialists understand this era.

First, Du Bois challenged racist Civil War and Reconstruction historiagraphy which argued that African Americans lacked the "capacity" either to fight for their own freedom or to build a society. He showed that during and after the war, African Americans agitated for their emancipation as strongly as any group of workers in U.S. history.

Second, Du Bois's historical materialist account of the Civil War and Reconstruction makes clear that class struggle was central to both. Du Bois used the term "general strike" to refer to fugitive slaves fleeing the plantation and withholding their labor power to help bring down the system.

Third, Du Bois's description of a "dictatorship of labor" was an idiosyncratic, but not incorrect, application of Marx and Engels's description of what a workers' democracy might become. It carried with it Marx's own hopes for expansion of workers' democracy after the Civil War. By using it, Du Bois was also extending his criticism of histories that tended to separate the lives of slaves from the lives of waged laborers.

DU BOIS' analysis of Reconstruction has, on many points, become the standard interpretation of the history of the Civil War and Reconstruction. On one point, though, Du Bois has been misrepresented.

Some subsequent scholars of Reconstruction tended to blame southern white workers for abandoning solidarity with Black workers in exchange for social and economic benefits they earned because they were white. These benefits, sometimes called "white privilege," were referred to by Du Bois in Black Reconstruction as the "wages of whiteness."

But Du Bois argued that racism benefitted not white workers, but the ruling class of the U.S. South, which used racism to divide and rule:

The political success of the doctrine of racial separation, which overthrew Reconstruction by uniting the planter and the poor white, was far exceeded by its astonishing economic results. The theory of laboring class unity rests upon the assumption that laborers, despite internal jealousies, will unite because of their opposition to exploitation by the capitalists...This would throw white and Black labor into one class, and precipitate a united fight for higher wages and better working conditions.

Most persons do not realize how far this failed to work in the South, and it failed to work because the theory of race was supplemented by a carefully planned and slowly evolved method, which drove such a wedge between the white and Black workers that there probably are not today in the world two groups of workers with practically identical interests who hate and fear each other so deeply and persistently and who are kept so far apart that neither sees anything of common interest.

Du Bois' analysis of the failures of Reconstruction explains why the Southern U.S. has historically been the least unionized region of the U.S.--and how formal systems of segregation that survived into the 1960s had roots in the collapse of Reconstruction. It also explains why racism, land dispossession and disenfranchisement--the strategies that overturned Reconstruction and established capital's dominance in the South--became tactics of U.S. imperialism, including the U.S. annexation of the Philippines, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Hawaii in 1898.

Reconstruction's end had other legacies, however.

The corrupt compromise between Republicans and Democrats that ended Reconstruction helped lay bare ruling class interests. Socialists and labor militants proposed for the first time in U.S. history a Workers Party (though it didn't last).

Labor also responded quickly when the railroad industry imposed a 10 percent cut in rail workers' pay. This set off the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the largest national strike in U.S. history to date. Union Army veterans were heavily represented in ranks of the strikers. Meanwhile, the federal troops withdrawn from the South at the end of Reconstruction were deployed against strikers--a stark lesson about the real concerns of the Northern industrialists.

In St. Louis, the rail strike was orchestrated by the Workingmen's Party. Strikers took control of the city for several days, with African American workers playing a prominent role in the strike. The employers responded with all-out brutality, hiring "deputy marshals" and Pinkerton men to help smash labor--by the 1880s, there were 30,000 Pinkerton men in the employ of bosses.

The last two decades of the 19th century saw pitched class battles and previously unseen levels of state and private repression. But the uprisings of labor in the 1880s and 1890s set the stage for the greater rise of the labor and socialist movement in the early 20th century.

THE HISTORIAN Robin Blackburn has written, "The frustration of 'bourgeois' revolution brought no gain to Northern workers or Southern freedmen. The double defeat of Reconstruction had suppressed black rights in the South and curtailed labor rights in the North."

It was in response to these setbacks that Engels wrote in his 1887 preface for the American edition of Conditions of the Working Class in England: "[T]he unification of the various independent bodies into one national Labor Army, with no matter how inadequate a provisional platform, provided it be a truly working-class platform--that is the next great step to be accomplished in America."

That step was not accomplished. The U.S. working class lives with the failures of Reconstruction to this day. As W.E.B. Du Bois put it:

If the Reconstruction of the Southern states, from slavery to free labor, and from aristocracy to industrial states, had been conceived as a major national program of America, whose accomplishment at any price was well worth the effort, we should be living today in a different world.

The attempt to make Black men American citizens was in a certain sense all a failure, but a splendid failure.

In our time, the struggle against ruling class austerity, the two-party duopoly, attacks on labor, and racism and police violence against African Americans, are all part of a tradition of battles waged by slaves, freed slaves and abolitionists, and the wider working class during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Like them, we have everything to gain and a world still to win.